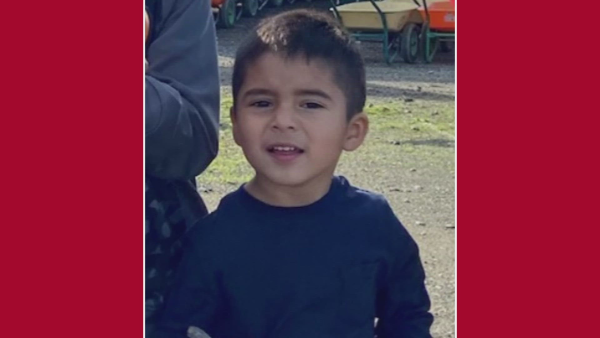

Painful timeline of Everett boy’s killing outlined in state report

Five days before the body of her 4-year-old grandson was found by a Pierce County highway, Maria Garcia called the state Department of Children, Youth, and Families to report that her daughter, the boy’s mother, was a danger.

Janet Garcia was using drugs and “acting crazy,” her mother told the department in March. She had been hitting Ariel Garcia and she had pulled his 7-year-old brother out of bed before taking him to a bar without his shoes on.

Maria Garcia’s efforts to save her grandson — whose mother stands charged with stabbing him 16 times — are detailed in a new review of how the Washington agency tasked with protecting children responded to her pleas for help.

The report lays out a painful timeline of events preceding Ariel Garcia’s killing, and adds insight into the grandmother’s desperate determination and how DCYF responds to a cry for help.

The report determined that given the information known at the time, the responding Child Protective Services caseworker responded appropriately. The review did not clearly identify any DCYF practices that may be amended due to the response.

Janet Garcia was charged with first-degree murder in April after a 24-hour manhunt ended when Ariel’s body was found on the side of the road. The day before Ariel was reported missing, his maternal grandmother, Maria Garcia, won

emergency guardianship of him and his 7-year-old brother.

Janet Garcia

pleaded not guilty and the Snohomish County Superior Court is awaiting results of a competency evaluation to determine whether she is fit to stand trial.

A fatality

review is required in child welfare cases when the death is suspected to be caused by abuse or neglect of a child who had recently received services from the department.

According to the report, Maria Garcia called DCYF on March 23 to report that Janet was “acting crazy” and using illegal drugs. She said Janet had been hitting Ariel, and said she had court paperwork to obtain custody of the boys. DCYF determined her concerns did not meet the criteria to open a case, as no allegation of

child abuse or neglect was reported, according to the review.

Maria Garcia’s primary language is Spanish, so the intake worker got assistance from an interpreter. The fatality review committee was “concerned” there may have been a language barrier in the way of getting enough detail. Intake report screening experts told the committee there is no way to ensure calls from non-English speakers can be routed to workers who speak their language, according to the review.

The day after Maria Garcia called, DCYF received a call from a law enforcement officer and a health care nurse after Janet took the children to the hospital. The nature of the children’s medical issue was redacted by DCYF, but the 7-year-old boy told the law enforcement officer his mother had dragged him by the neck down the stairs, according to the report. That report met DCYF’s criteria for a “

family assessment response,” which is an alternative to a traditional case for “lower risk allegations of maltreatment,” according to DCYF

policy.

That alternative response, which first rolled out in 2014, does not open an abuse investigation but offers resources to the family and identifies the family’s needs. The department must respond within 72 hours in one of those cases.

The state has sought to keep families together by prioritizing providing services over removing children. The shift in approach has resulted in the number of children in Washington’s foster care system dropping by

half in the past six years.

Two days after the family assessment response was opened for the Garcias, DCYF received a written law enforcement report stating that the fire department came to the home when Janet reportedly pulled her 7-year-old out of bed aggressively. It also said that law enforcement had responded to the bar to which Janet had reportedly made her 7-year-old walk without shoes on, hurting his feet. That report “met screening criteria for another” family assessment response, the review stated.

The next day, March 27, a DCYF caseworker met Ariel’s older brother at his school. The boy said he felt safe at school and at home, and his school counselor said they did not have concerns about the family.

That same day, Janet’s ex-boyfriend’s mother reported Ariel and his mother were missing from the Everett apartment where she had been letting them stay, according to probable cause documents filed in Snohomish County Superior Court. A prosecutor wrote there was a large bloodstain and a child-sized bloody handprint in the living room, according to court documents.

That night, the caseworker learned from a law enforcement officer that Ariel was missing and that Ariel’s brother was with his grandparents. The caseworker spent the next day attempting to find Ariel’s father and speak with his maternal grandparents.

A 24-hour manhunt ensued. An Everett police officer spoke with Janet Garcia over the phone, and she said Ariel got injured after he fell out of bed, according to court documents. She told the officer she had dropped Ariel off in Portland, then said it was Seattle, before hanging up, prosecutors allege.

Clark County Sheriff’s Office deputies located Janet Garcia in a mental health hospital, where she had blood on her shoes and shirt. A law enforcement officer called DCYF, which opened a “risk only” CPS investigation, which finds a child is at “imminent risk of serious harm.”

Cellphone data showed her phone near Joint Base Lewis-McChord, where video footage recorded her in a gray hoodie retrieving an object wrapped in white from her trunk, according to the documents. Law enforcement found Ariel on March 28, dumped over a fence line at JBLM with stab wounds in his chest, abdomen and back. A law enforcement officer called the caseworker again to inform them Ariel had been found.

According to the fatality review committee report, the family assessment response unit followed the right steps, but it did note one persistent issue: The unit had a high-volume workload when the Garcia case came in.

The average goal for caseworkers is to have eight to 10 new cases per month, but the caseworker on Ariel’s case had been assigned 15 cases in the month prior and 12 new cases that month. DCYF’s current recommendation is five, not more than eight new cases per month, with a maximum of 12 open cases at any one time.

The Washington Federation of State Employees, the union representing CPS workers, has

said for years that caseworkers are stretched thin.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/AXQTGQQLKZCUJPRG2K5OJUUWFY.jpg)